Cyd Charisse could do everything—sing, act, and dance like music made flesh—and those impossibly long legs became legend. But the woman who looked born for the spotlight began as a skinny, sickly Texas kid named Tula Ellice Finklea. After a bout of polio, her parents put her in ballet “to build me up,” she’d say later. It did more than that: it gave her a life. Her brother’s mispronounced “Sis” became “Sid,” and when Hollywood finally came calling, producer Arthur Freed burnished it into the name the world remembers—Cyd.

She grew up in Amarillo, where dust and wind were more familiar than footlights. Ballet remade her body and set her compass. By her teens she was studying with serious teachers, first in Los Angeles and then abroad, soaking up classical line and épaulement that would become her calling card. On early ballet tours she briefly tried on Russian-sounding stage names (as many American dancers did then), but the essence never changed: a cool, unfussy elegance wrapped around fierce musicality.

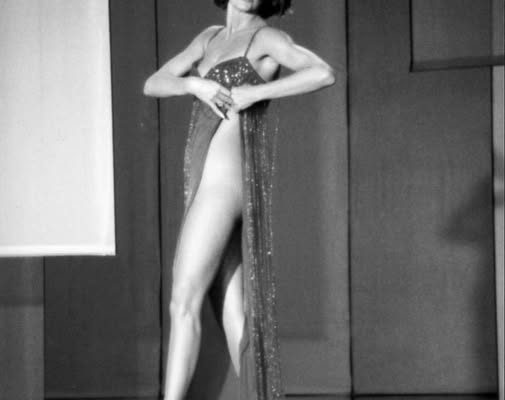

Film found her through dance, not dialogue. She turns up first like a shimmer—uncredited assignments, specialty numbers, that poised girl who moves differently from everyone else. MGM, in its imperial phase, signed her and let her ripen. A quicksilver appearance opposite Gene Kelly in Ziegfeld Follies (1945) hinted at what was coming: even in a few bars of choreography, her line read across the room. Then came the moment that burned her into movie history—gliding through the “Broadway Melody” ballet in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), hair jet black, dress a poisonous shade of green, legs seemingly endless, saying everything without a single spoken line. She arrives like a dream and vanishes like one too, but the imprint stays.

People love to argue Fred Astaire versus Gene Kelly, and Charisse is the rare dancer who made both men look even better than they already were. With Kelly she could meet brute force with silk-covered steel; with Astaire she could turn breath into phrasing. In The Band Wagon (1953), “Dancing in the Dark” is almost nothing—no trick steps, no camera acrobatics, just two people walking into a waltz in Central Park—and yet it feels inexhaustible because of what Charisse brings: the slight hesitation before giving in, the way her back tells you what her face won’t. Astaire famously called her “beautiful dynamite.” She returned the compliment without choosing sides—like comparing apples to oranges, she’d say politely. The truth is she answered two different musical gods with equal eloquence.

What made her different wasn’t just those legs (publicists loved to say Lloyd’s of London insured them for a million dollars). It was the way she phrased movement. You could freeze any frame and see the ballet training—the long, clean line from shoulder to wrist, the carriage, the turnout—but she didn’t dance ballet steps; she breathed through jazz and modern shapes until they felt inevitable. Watch how she lands a weight change, how her foot finds the floor like a cat, how a turn finishes with the lightest whisper of a head. Where some dancers sell you velocity, Charisse sells you time—how to stretch it, suspend it, then snap it like a silk ribbon.

MGM kept her busy even as the musical began to wobble in the 1950s. Highlights pile up: the noir-tinted danger of her vamp in Singin’ in the Rain; the cool sophistication (and sly humor) of The Band Wagon; the tart melancholy of Brigadoon (1954), where her epic line softens for a Highland romance; the urban bite of It’s Always Fair Weather (1955); the urbane fizz of Silk Stockings (1957), where she updates Garbo’s Ninotchka with deadpan wit and lethal glamour; the smoky, grown-up allure of Party Girl (1958), whose nightclub numbers doubled as character studies. Even when the script shortchanged her, the choreographers didn’t: they gave her space, knowing the camera liked to sit back and watch.

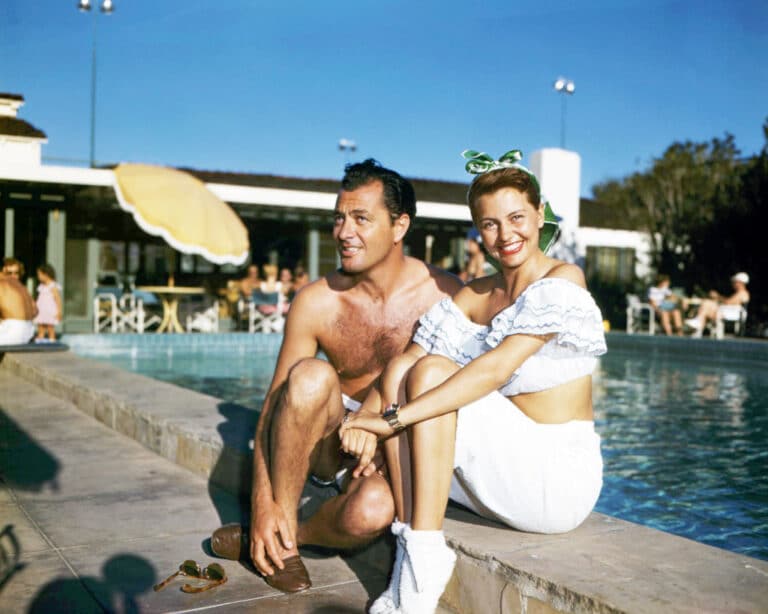

Offscreen she was a studio’s dream: punctual, prepared, and allergic to scandal. She married her former dance teacher, Nico Charisse, very young; they had a son, Nico Jr. In 1948 she married singer Tony Martin, and that second marriage lasted six decades—practically a record in Hollywood. While her screen image was all smolder, colleagues remembered the shy, wry woman who preferred home over parties, rehearsal clothes over gowns, and orange juice over martinis. When the movie musical ebbed, she pivoted without self-pity—television variety shows, European films, then the stage. She and Martin toured a polished nightclub act; in the 1990s she wowed Broadway audiences in Grand Hotel with the kind of authority you can’t fake because it’s built out of years.

A life brushed with stardust isn’t spared sorrow. In 1979, American Airlines Flight 191 went down after takeoff from Chicago, killing everyone aboard—including Sheila Charisse, the 36-year-old wife of Cyd’s son. The catastrophe became one of those American tragedies people still whisper about. For Charisse and her family it was a private hole in the world that never fully closed, a reminder that grace under pressure isn’t only a stage trick.

Still, she kept working, teaching, mentoring, reminding younger dancers that glamour without craft is just a dress. Honors found her late: in 2006 she received the National Medal of Arts, official recognition of what dancers, directors, and audiences had known for half a century—that she helped define an art form on film. She died two years later, at 86, after a heart attack. Tony Martin followed in 2012. Their long duet ended; the music didn’t.

If you want to understand what she did that no one else quite does, look closely at three moments:

-

“Broadway Melody” (Singin’ in the Rain) — She moves like a blade wrapped in satin. The famous green dress isn’t just costume; it’s choreography. The slit reveals the engine, the bias cut turns every step into a line drawing. When she folds into Kelly’s arms, it reads as surrender, but watch her spine—it never collapses. Power choosing softness.

-

“Dancing in the Dark” (The Band Wagon) — No pyrotechnics. Just breathing, and a walk that becomes inevitability. The way she extends a leg and lets the heel kiss the pavement tells you what the lyric can’t: that love is rhythm, not argument.

-

“Silk Stockings” title number — Charisse weaponizes stillness. The comedy is deadpan; the control is ferocious. She lets you see the soldier inside the satin, then laughs with you at the reveal.

Beyond the set pieces, there’s the larger consequence of her presence. Before Charisse, Hollywood’s default for a leading lady in a musical was “ingenue who can move.” After Charisse, choreographers started writing for a woman who could carry the dance language the way Astaire did—who wasn’t simply an ornament, but the axis. Directors learned to let the camera linger; editors learned to cut less; partners learned to listen. She made space for the next generation—dancers who weren’t afraid to be statuesque, modern, complicated.

The myths are fun—the million-dollar legs, the cool hauteur, the emerald dress that launched a thousand crushes—but the deeper truth is better. Cyd Charisse showed that strength can look like silk, that elegance can be athletic, and that a story can travel down a calf and across an ankle to land, softly, exactly on the beat.

Decades on, the films still hum. Put on The Band Wagon and let the park turn to ballroom. Cue up Singin’ in the Rain and watch the green dress edit itself into your memory. Revisit Silk Stockings and see how a raised eyebrow can be choreography. You don’t need nostalgia to enjoy her; you just need eyes.

Her language was movement. Her legacy still dances